|

|

A few months ago I sat down for a conversation with a woman of color who is in leadership at a Christian organization. She responded to my research questions about what she hopes racial justice would look like in her community. When I asked what she sees white Christians doing (or not doing) toward those ends, she paused and took a breath before she spoke, choosing her words carefully.

“Honestly, like, the most gracious thing I could say is, I think they care.” She explained, “For the most part, I’ve never heard any of them say anything that actually feels daring or risky. Ever. … And I’m like, you know, my very existence is a risk every day.”

She was not the only one who responded in this way. My method for including white people in research involved asking people of color to recommend white Christians to interview. I suggested they think of the kind of white people they might recommend as a mentor for some other white person who is new to racial justice. More than a few thought for a good while before saying, “I’m not sure I know any.”

This is not new.

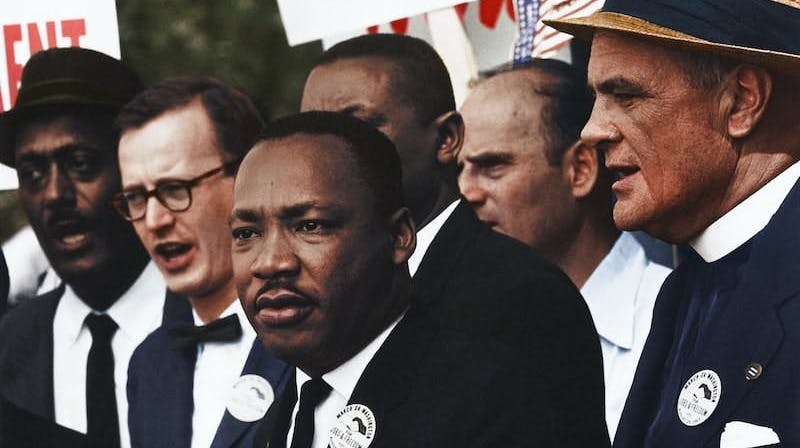

In 1963 Martin Luther King wrote from a jail cell that he had hoped more white people would be willing to be “extremists for love.” His disappointment wasn’t with outright enemies to Black civil rights—it was about white moderates, liberals, and especially white Christians. He reflected,

He repeated again a few pages later, “Maybe again, I have been too optimistic.”

I have started noticing how often this question of whether to be optimistic runs through writing on racism. Much of critical race theory is a reflection on how to hope without optimism. Whatever you may understand of critical race theory, this is a question worth asking: How optimistic should we be about racial injustice?

False optimism produces disappointment, and disappointment is perhaps the most fitting description of what’s happening among people leaving the church today. King wrote, “I am meeting young people every day whose disappointment with the church has risen to outright disgust.” You’ve probably seen the same. I am reminded of a research conversation with a man who said he’d left some gatherings of white Christians lately “wanting to throw up in my mouth. I mean, it’s just, I see so many of my friends leaving the church, and I feel like, totally, I would leave that too.”

King isn’t flippant about the pain of watching white Christians reject racial justice.

More and more of us can relate to the quote attributed to the fourth century theologian Augustine, “The church is a whore, but she’s my mother.”

So where does this leave us? Should we stop expecting white people to change? Maybe we need to be something like “a really hopeful pessimist or a crabby optimist,” as the woman at the start of this newsletter called herself. Cornell West calls it learning “hope without optimism.”

Whatever you call it, notice that giving up optimism doesn’t mean giving up on hope. In fact maybe it leads us to a truer kind of hope.

One way King rekindled that hope was by remembering that the people scratching out paths for justice throughout history have usually been “small in number but big in commitment.” This is true of white people pursuing racial justice then and now. “I am thankful,” King says, “that some of our white brothers have grasped the meaning of this social revolution and committed themselves to it. They are still all too small in quantity, but they are big in quality.”

And here’s the quote that I’ve been carrying with me since I reread his letter a few weeks ago. Describing the few “noble souls from the ranks of organized religion” who “have broken loose from the paralyzing chains of conformity and joined us as active partners in the struggle for freedom,” he wrote,

Whatever your faith or background, I’m grateful to be carving those tunnels together with you.

|

|

This is the third of a series of newsletters based on Dr. Martin Luther King’s Letter from a Birmingham Jail. You can read my previous posts here, or better yet, read King’s whole letter here.