Ok, so imagine you’re part of a predominantly white organization. Imagine you’d like that organization to become more diverse. Cool. Now imagine you’re choosing photos for the organization’s website. Whose faces do you include? What percentage of people of color should appear?

|

|

Including a higher percentage of people of color in communications than in the organization itself has been shown to sometimes be an effective way to push a company in a helpful direction. But there’s a risk. That’s where today’s fancy term comes in—racial capital.

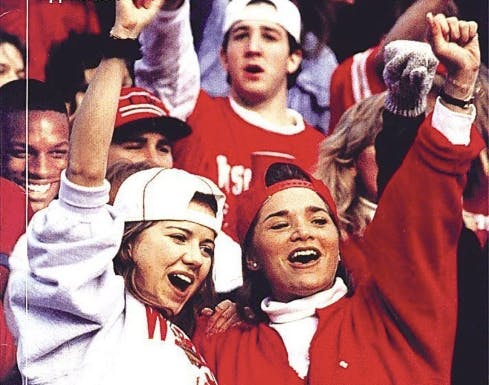

When the University of Wisconsin-Madison created the image to the right for a 2000 admissions brochure, surely they wanted to prioritize diversity. But look closely. The face of the Black student, whose name is Diallo Shabazz, doesn’t quite match. That’s because the brochure designers photoshopped it in. Shabazz had never even attended a football game.

It doesn’t take photoshop to bend over backwards to overrepresent diversity. Studies have shown that most predominantly white colleges overrepresent diversity in their communications.

Which raises an important question. When diversity is over-portrayed, who wins?

If the organization is a great place for underrepresented people to thrive, everybody wins.

But regardless of whether they thrive, who wins? White people at that organization benefit from signaling to the world that they’re doing this diversity thing well. And importantly, they accrue those benefits not from necessarily doing anything well. They gain from what people of color contribute, knowingly or unknowingly.

The term racial capital, coined by Nancy Leong in a 2013 Harvard Law article, describes situations like this in which people of color themselves become capital—a kind of investment that brings earnings to somebody else. Leong defines racial capitalism as “the process of deriving economic and social value from the racial identity of another.”

The sneaky thing about racial capital is that it shows up in groups that value diversity. The researchers Michael Emerson and Gerardo Marti found racial capital to be common in churches. White pastors who had more people of color in their congregations or on staff were assumed to be “diversity experts,” earning them gigs as speakers and authors. There’s nothing wrong with that if they were indeed experts, but in Emerson and Marti’s findings, these so-called experts often had little idea how to recreate diversity or create conditions in which underrepresented people could thrive. Having a mix of skin tone, gender, social class, ability, or other markers of diversity at a given point in time does not mean everyone is thriving.

Racial capitalism puts people of color in situations where their dignity and integrity are objectified and commodified. It expects them to perform their identity in certain approved ways. You can probably draw some parallels between racial capital and enslavement, in which black bodies and their capacity to work and reproduce were the direct source of white income. This is not something to take lightly.

So how to address racial capital?

The solutions to racial capital don’t involve doing away with the goal of diversity. Instead, they require expanding that goal. Leong writes:

She also recommends acknowledging racial capital when it’s happening. Name instances when white people benefit from the presence of people of color without people of color gaining to the same extent. White people need to ask, are they choosing to belong to organizations that appear numerically diverse because it makes them look like better people, or are they actively creating groups where everyone thrives?

Organizations can also work to involve underrepresented people in decisions about how they are represented in company media. Including the same handful of underrepresented individuals in every media post doesn’t cut it. And if your organization disproportionately asks underrepresented individuals to represent the company as spokespeople or committee members, hold the organization accountable for truly compensating that time and effort.

Every organization needs to consider how to make the benefits of diversity accrue for underrepresented people themselves, not just for dominant individuals. That requires identifying problem areas in the organization, actively naming goals, and measuring progress toward those goals.

I hope that knowing the term racial capital gives you a tool to see and change a pattern that is all too common—settling for the appearance of diversity without fostering communities where everyone genuinely thrives.

|

|