Today in recognition of the holiday commemorating Martin Luther King, Jr., I decided to read some of his writing. I began with a piece that is rightly among his most famous: the Letter from a Birmingham Jail.

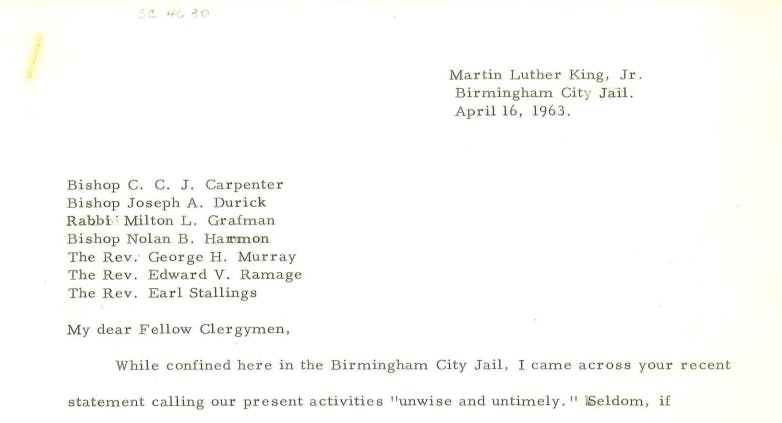

I especially love reading this letter from the scan of King’s original typed copy. Seeing the yellowed edges and occasional hand-written corrections to typos (which are shockingly few, considering), I can imagine this brow-furrowed leader sitting with a borrowed typewriter in a bare cell, pausing now and then to pray in the midst of a whirlwind of spiritual flow.

|

Opening lines of King’s letter from the Birmingham jail. |

As usual, King’s writing reminded me he was not just some great speech-writer but one of the most brilliant and spiritually alive people we’ll ever encounter. Reading today I quickly jotted down enough ideas for not just this one letter to you but two more, which I plan to send in the coming weeks.

Let’s start by paying attention to two words in his letter: tension and negotiation. King says it “may sound rather shocking,” but from his standpoint, “I am not afraid of the word tension. I have earnestly worked and preached against violent tension, but there is a type of constructive nonviolent tension that is necessary for growth.”

His desire for tension reminded me of a conversation I had recently with a woman who was telling me why she chose her church. “There’s no drama,” she said. Her previous church had too much “drama,” and she kept expecting some conflict or drama would rise from beneath the surface here, but it never did. “This church is apolitical,” she added.

Many of us know all too well what church “drama” can entail. Christians as well as anybody can be cruel, bickering, shaming, or abusive, and sometimes churches even create dysfunctional systems that foster these. No one wants more of the terrible sources of church drama.

And neither does King want more of injustices that cause tension. But King makes clear that when there is no tension—no drama, as this woman called it—the tension may merely be hidden beneath the surface. He writes, “We who engage in nonviolent direct action are not the creators of tension. We merely bring to the surface the hidden tension that is already alive. We bring it out in the open where it can be seen and dealt with.”

Then he lunges into a metaphor that gives me a twinge of physical disgust, and perhaps that gut-turning feeling is a reminder of what we might need to feel toward racial injustice: “a boil that can never be cured as long as it is covered up but must be opened with all its pus-flowing ugliness to the natural medicines of air and light, injustice must likewise be exposed, with all the tension its exposing creates, to the light of human conscience and the air of national opinion before it can be cured.”

The Latino theologian Justo Gonzales in his book Mañana argues that there is no such thing as an apolitical church. If your church or organization seems apolitical, perhaps it merely matches your own politics so closely that you do not have to notice. Bible interpretation necessarily takes a stance about who has power and they use it. The only real option in Biblical interpretation is whether or not to try to figure out how God regards power.

|

|

One of the church leaders I interviewed for research gave an analogy of a crock pot (which they learned from this research). If stew in a crock pot is not bubbling at all, it’s time to turn up the heat. If it’s bubbling so wildly things are starting to burn, adjust the temperature down a bit, but not all the way. Being a leader in pursuit of racial justice means always making adjustments to keep a rolling boil.

Finally, I’ll mention that all this sounds well and good, but I haven’t mentioned yet what I believe is the hardest piece of all in King’s plan. He says he creates tension in order to push people into negotiation. I wonder, how often does tension around racial justice lead to negotiation today?

In the decades since King’s letter, I think we’ve gotten ever better at creating tension—after all, tension draws clicks and sells news. But I don’t think we’re any better at stirring up the particular kind of tension that leads to negotiation. We’re good at following tension into withdrawal, rage, or dehumanizing mockery of the “other.” King says it moving from tension to negotiation will be difficult. It will, in fact, require a daunting step he calls “self-purification.”

Are you willing create the kind of tensions that lead to dialogue, negotiation, and ultimately good social change? You might stir up some “drama,” but press on. Thank you for being people who keep the pots boiling.

|

|